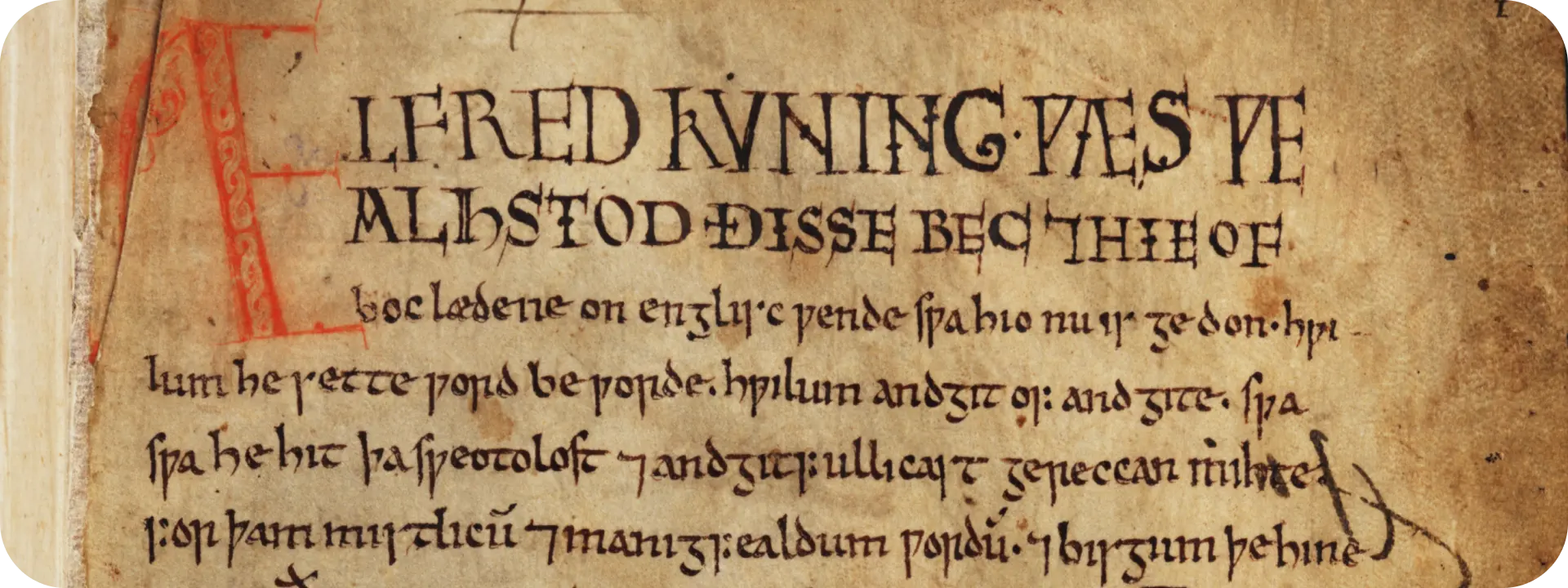

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 180, fol. 1r. Image reproduced from the Digital Bodleian under CC BY-NC 4.0 Deed

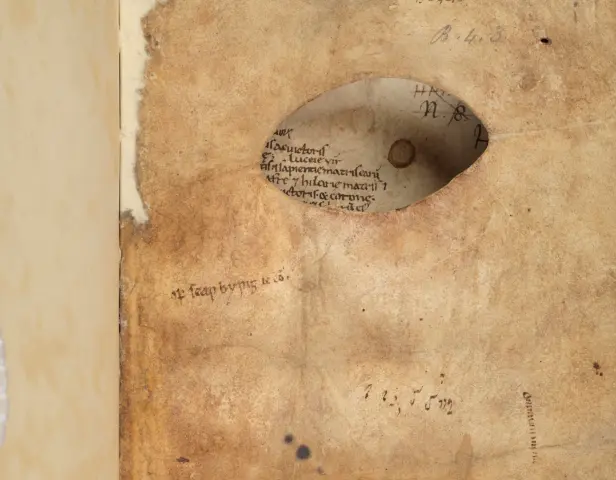

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 180, fol. 1r. Image reproduced from the Digital Bodleian under CC BY-NC 4.0 Deed

Searobend links together metadata about medieval manuscripts, works, texts and scribes from sixteen key resources for the study of English Language texts, 1000–1300. These sixteen resources are listed here. That metadata comprises information about when and where particular manuscripts are thought to have been produced, what works they are thought to contain copies of, when those works were composed, which scribes were involved in their copying, and much, much else besides.

View ResourcesSearobend offers users three main ways to engage with the data about manuscripts, works, texts and scribes it links: free-text predictive search (so that you can type ‘Wulf’, and be offered the option to search for ‘Wulfstan’ and any other ‘Wulfs’ in our data), a structured advanced search (where you can search for ‘Wulfstan’ and a manuscript of eleventh century date, now in the Bodleian, for instance, or manuscripts Ker dates one way and Scragg another), and an option to browse by different categories (e. g. through a list of the supposed place of origin of the manuscripts covered by Searobend). Users are also encouraged to look at the various visualisations we have built from the data, which attempt to show the extent and geographical spread of English language writing between 1000 and 1300.

View Resources

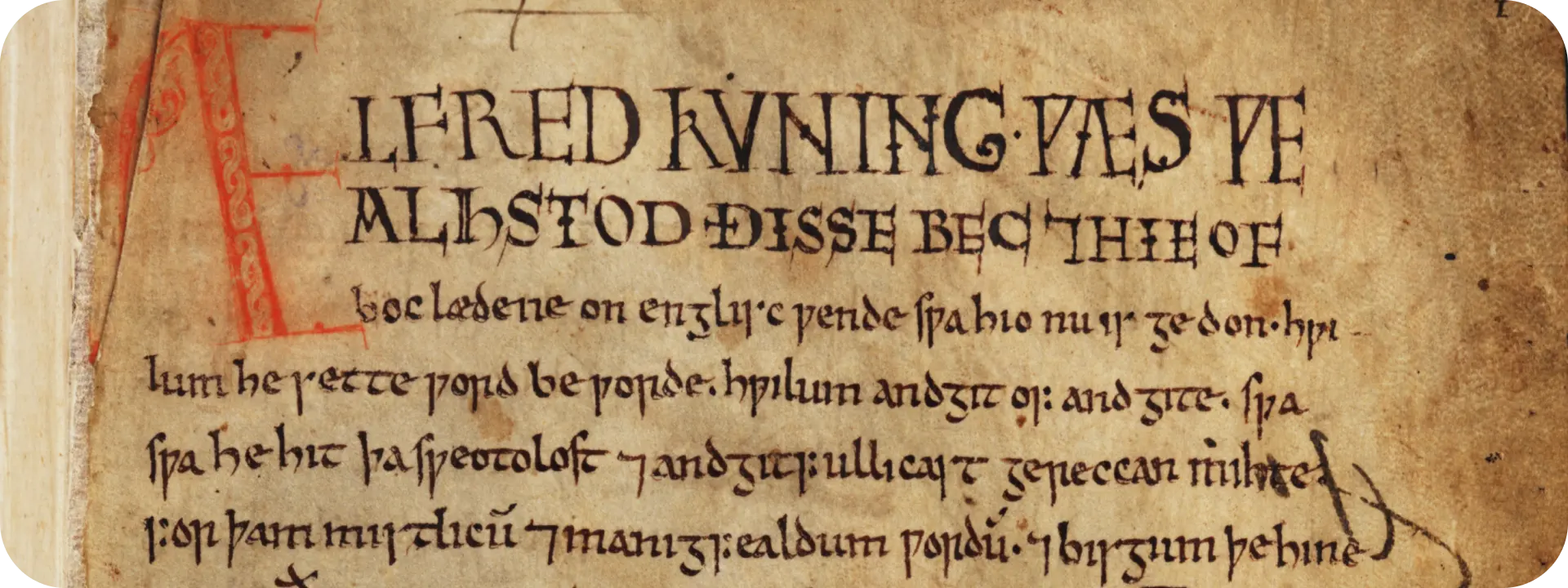

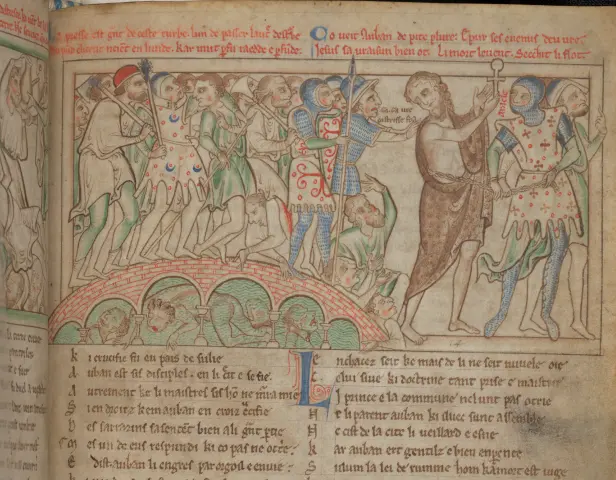

Cambridge, Trinity College, R. 17. 1 (987), fol. 281r. Reproduced by Permission of Trinity College Cambridge under CC BY_NC 4.0 DEED licence

The approach Searobend adopts to the challenge of connecting the sixteen resources comes from Computer Science, and is the technology of Linked Data. Linked Data techniques enable us to articulate that when two or more resources are talking about a particular manuscript, they are talking about the same thing and, more importantly, operate computationally across that connection, for while a human can easily see that one manuscript in one resource is the same as one manuscript in another resource, to do that for all 400 manuscripts in both resources is a serious challenge, let alone to do it for fourteen more resources and several hundreds of other pieces of information beyond manuscript shelfmark.

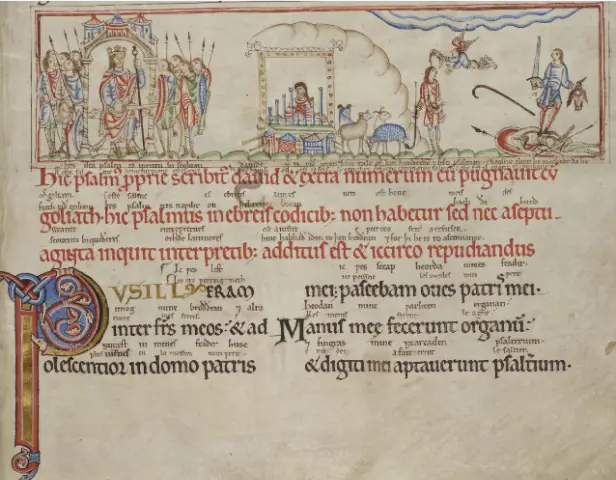

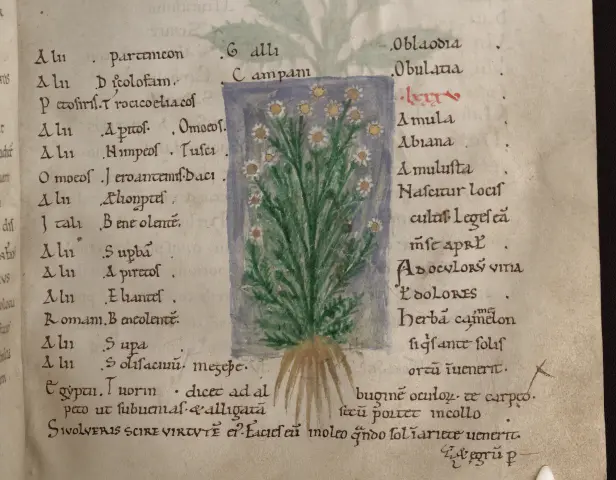

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole 1431, fol. 6v. Image reproduced from the Digital Bodleian under CC BY-NC 4.0 Deed

The sixteen resources describe some features of these manuscripts, works, texts and scribes according to different parameters. To take one very simple example, Ker’s Catalogue of Manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon describes the Cotton manuscripts as being in the British Museum (which they were in 1957, when the Catalogue was published); Gneuss and Lapidge’s Bibliographical Handlist of Manuscripts and Manuscript Fragments Owned in England up to 1100 describes them as being in the British Library, where they now are. Because of these differences in how the sixteen resources describe what we regard as the same thing, Searobend had to develop an ontology (or controlled vocabulary), on to which the information in each of the sixteen resources could be mapped.

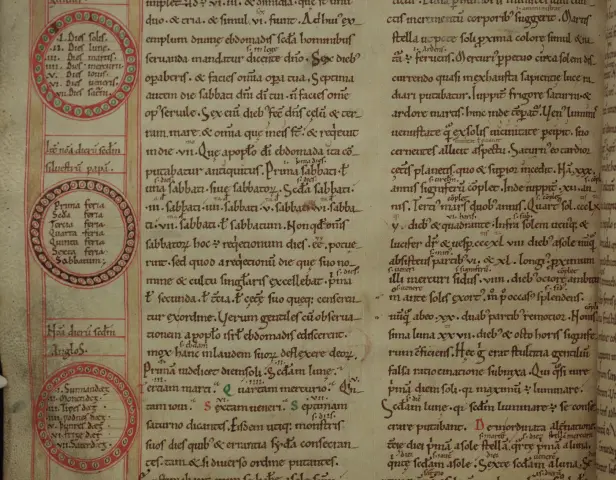

Oxford, St John's College, MS 17, fol. 71v. Image reproduced from the Digital Bodleian under CC BY-NC 4.0 Deed

Four key concepts in the ontology are manuscripts, works, texts and scribes. Manuscripts are handwritten codices (or fragments) that survive today, or existed in the past. A work is a piece of writing (of any length) produced by a person at a particular time. Works survive only in texts, witnesses to a work. So De initio creaturae is a work, a piece of writing composed by Ælfric of Eynsham. That work survives in thirteen manuscripts, including London, British Library, Royal 7 C. xii, fols. 4-9. Fols. 4-9 therefore offer a text of the work. A scribe is the person imagined to be responsible for copying a work (or part text) into a manuscript.

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 130, fol. 44r. Image reproduced from the Digital Bodleian under CC BY-NC 4.0 Deed

The concept of manuscript needs further definition. Searobend distinguishes between physical manuscripts that exist today and notional manuscripts, which have been reconstructed by scholars. London, British Library, Royal 7 C. xii is a physical manuscript: one could travel to London, go to the Manuscripts Reading Room in the British Library, and ask to see it (albeit to be directed in the first instance to the digital facsimile). Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 197B (with London, BL, Cotton Otho C. v + Royal 7 C. xii, fols. 2, 3) is, by contrast, a notional manuscript, an early-eighth-century gospel book reconstructed by scholars from disjecta membra now in different physical manuscripts, including Royal 7 C. xii. One could not walk into any library and ask to see it. In fact, our ontology actually sees individual scholars like Ker or Scragg as always discussing their notions of manuscripts, rather than physical manuscripts themselves (so that Ker no. 288 is Ker’s notion of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole 328, not Ashmole 328 itself). This helps us keep individual scholars’ statements about the structure, date, origin and provenance of these manuscripts apart.

Dublin, Trinity College, 177, fol. 36r. Copyright The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Notional manuscripts are creations of scholarship; they do not exist. The same is also true of works. If one wants to cite the work De initio creaturae, one today usually goes to Clemoes’ Early English Text Society edition of Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies. He there with minor emendations prints the text of Royal 7 C. xii, but it is an assumption (eminently defensible, but nonetheless an assumption) that the text in Royal 7 C. xii represents or best represents the work Ælfric is believed to have written. In the case of other homiletic writings, especially anonymous ones, different authorities might have different views on what works once existed, and which works the texts on particular folios of manuscripts witness.

Dublin, Trinity College, 174, fol. i r. Copyright The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

For this reason, Searobend stores the information from each of the sixteen authorities in a separate knowledge graph. For some categories of information, it is therefore possible to compare what different authorities say, for instance how Ker divides up scribal contributions to a given manuscript compared to Scragg, and whether they assign the same dates to them. For others, our restriction to sixteen resources and policy of only including the data in those sixteen resources and resisting the temptation to supply gaps or alternatives ourselves, means only a single view is available. For instance, the only view of the surviving inventory of ‘Old’ English works in Searobend is that of Cameron List and its various revisions (with no recognition that the text on particular folios of manuscript X has been considered by some scholars a witness to a lost anonymous work rather than a work by Wulfstan, the way it is presented in the Cameron List).